The inspirational life of a democratic revolutionary woman: Eleonora Pimentel De Fonseca

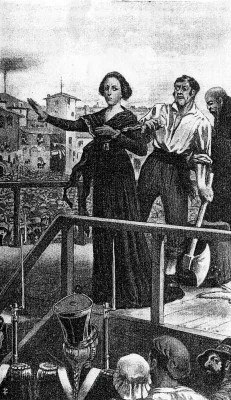

“ Forsan et haec olim meminisse juvabit”,(maybe one day it will be helpful to be reminded of all of this), these are the last words of Eleonora Pimentel De Fonseca standing on the headsman’s block before her execution after the fall of the Napoli Republic in 1799.

Since I first started to imagine this blog, I thought that I would open by writing about Eleonora, a brave woman from my land who challenged with her intellect and fierce determination for truth the conventions of the time and who became one of the central personalities of the revolution which brought the birth of the Neapolitan Republic in 1799.

There are several reasons why Eleonora’s history is absolutely fascinating and totally actual: because of her beliefs that find resonance today, her passion, her drive and because of the reasons for her dramatic end.

She lived in a challenging and dramatic time. As a woman she faced convention and she was able to come out from a hard story of domestic violence and a brutally abusive husband (getting divorced in a time where women were certainly not free to take these decisions) but she was also a woman who made and imagined a revolution through an idea of intellectual life which meant to be open and sharing.

In fact we’re living the dramatic time of the pandemic which asks revolutions, but we’re instead witnessing our lives submissive to the command of the scientists, who are as unreliable in their certainties as their panicked political masters, improvising each day in the face of catastrophe. There aren’t the social dynamics which try to figure out new worlds. And most of all women are put more and more socially and economically in a corner, because they are the less employed, and paid, and the ones forced to care for children with the schools closed. In front of people asking for changes, and extending their claims of the moment to include the economy, politics or ecology, what seems pressingly evident is the need of knowledge as tool and of a sharing knowledge as democratic basis.

Eleonora Pimentel lived and studied in Naples in a time in which the city was the capital of the Kingdom of Naples and one of the cultural capitals of Europe. She had mail correspondence with Voltaire and Metastasio who both admired her intellect. It was a very vivid and international intellectual world in which she fast became a protagonist. Her world was in ferment with ideas of liberty, equality and freedom from oppression. But with the bloody end of the French Revolution and the establishment of the French Directory the king, Ferdinand IV, and his wife Carolyn, who was the sister of Marie Antoinette, suspicious of illuminism and of intellectuals, determined on a policy of harsh repression.

Without describing the international political dynamics and the battles which were necessary, I believe this revolution and the ideal on which it was based are still important and capable of giving a true understanding of democracy.

If the political effect was to change the form of government with the pushing out of the monarchy and the setting up of the Republic of Naples, what was sustained as central to this shift was education, and an awareness of what would come to be called later in the century the proletarian population. A republic that was for all of its citizens

The work of Eleonora was cardinal for this goal: she was the editor of a news sheet called “Monitore Napoletano”. She wrote it in Neapolitan dialect so that it could be spread through all classes and to reach those who were able to speak only Neapolitan. It was a revolution moved from an intellectual ”elite” but totally focused on the idea that the core of every democracy was the education of all the citizens: in fact, in the constitution act of the Republic, which even in a revolutionary time can be seen to be extraordinarily enlightened, culture was central and the republicans imagined a constitutional court (the first ever realized) that was meant to supervise and to ensure that the democratic sharing purpose would always be followed. (I guess that the reasons for my fascination are pretty evident)

The Republic lived only five months (from the 23rd of January to the 13th of June 1799), it was overthrown by the resurgent Spanish monarchy with the support of the lower classes for whom the Republic had fought. After an armistice in which it was agreed that the rebels would not be punished, the king reneged on his promise and killed them all: all the intellectuals and activists, of every age, all who had stood for the Republic. Even the Tsar of Russia, who had helped the king Ferdinand (his cousin) in his overcoming the Republic, asked in vain that the king should show clemency believing that to kill so many would leave Europe more poor.

This dramatic history left Naples weak, the murder of several generations of intellectuals and the erasing of the intellectual life of the city, and its dream of emancipation and shared meaning, was a catastrophe that would resonate through the century and beyond. The city did not recover and, less than 100 years after, it was easy prey to the despoliation of its economy and culture during the process of the unification of Italy.

Eleonora was a warrior of culture, she believed in its emancipating power but she was blocked by the time and by the politics and the economic strategies of a monarch who used the poorest in their desperation to serve his purpose. There was not time for the process of the social awareness for which she had fought to take hold. The consequences of this failure can be seen to have effect even until today, in the city, the region, and beyond it, after more than 200 years.

I believe that the tragic parabola of The Republic of Naples’ and the inspirational life of Eleonora Pimentel De Fonseca can be a very clear lesson for our time where women are still put apart from the war room. It’s a lesson for the intellectuals who fall very often into the trap of elitism and separation, and it’s a lesson for all of us who imagine that the revolution came from the other or from weapons when the necessary step is the sharing experience and the belief in the awareness of our social and political condition and potential.

(As an afterword, I have written about a Republic of Naples once before and it was attacked by monarchists (!), derided as historical nostalgia, or of colluding with the divisive regionalism that continues to be a condition of Italy today. It is none of these things. The Republic of Naples is about the present, yes, informed by the past but a past understood from our present, it is a state of intellect and shared meaning, it is the place of the commons and of the acknowledgement of relation)