A few months ago “La Dolce Vita” by Federico Fellini was celebrated 60 years from its premiere. But I am not writing this today because of the anniversary or because it still signifies enough to be remembered 60 years on. I am writing because it’s my favorite movie, my personal winner in my top ten of the many thousands of films that I, like most of my generation, have seen in my life. Everyone – and pretty much certainly during a first date! – gets to face at a point in the conversation the question “What is your favorite movie?” (Which is funny because I am thinking do I like this guy enough to…and we are talking about old movies) and I have never had any doubts, “La Dolce Vita” is my favorite movie. I love it.

The film opened on the 2nd of February 1960 at the cinema Fiamma in Rome and, despite the time and the black and white, it doesn’t look old and it’s still incredibly contemporary and actual.

There are several reasons for my passion and one of the reasons is certainly the historical time in which it was imagined and filmed and I am not here talking about what is described in the movie, I mean the cultural and social time lived in Italy for 40 years, from the end of the Second World War to the end of the 70s. And it’s consequences, today.

Actually, this will be one of the narratives of my blog, but for now I will focus on the end of the 50s and the beginning of the 60s, the time in which the movie was imagined, constructed, and released.

It was a time in which the country was living a great economic expansion no longer constrained by the overwhelming imperatives of reconstruction, standing on its own feet, no matter the baleful shadow of the US in the affairs of state, and even able to achieve independence in energy with the ENI (a public company). It was the time in which, in 1957, the Economic European Community was founded, shaped and brought into being through the work of people like Alcide De Gasperi and Altiero Spinelli, based on the values of peace and collaboration. Italy, and Europe, emerging from the ruins of war and the rebuilding after it, was released into a new possibility and hope of what could be made.

Rome, then, was a center of cultural life and of innovative cinema, when it was possible to have as script writers intellectuals like Ennio Flaiano or Pier Paolo Pasolini, as in the case of “La Dolce Vita”, and when we could have found at the café “Rosati” artist, intellectuals, writers debating Italy, fiercely, art and the future.

And this was the time in which, abandoning his interpretation of Neo-Realism, Fellini moved to what was seen as a more contemporary aesthetic, an aesthetic that expressed the time and, most of all, what Italy was, and the society behind the sparkling seductive surface of the economic boom: in fact, this is another aspect of what makes me love this film so much, the fact that it’s an incredibly rational dramatic story, no matter that the director kept describing the film as a comedy.

Italy, beyond its borders, is still sometimes described as the country of la dolce vita. What is meant is that it is imagined as a place where it’s possible to live a light and joyful life. Fellini’s movie, completely misunderstood, is often used to support this stereotype by those who apparently believe that it is a place where men adore women like Marcello does in the film (trust me, it’s not true! Glorious Marcello and idiotic world!), or where there is a lazy sybaritic desire to party and to enjoy life as much as possible.

If it’s true that, for example, we have shaped through centuries a kind of lifestyle that, because of the urban structures of small towns built up of public spaces, there is a more openly shared space of social relations, and if it’s true that there is a collective obsession with food which asks time for cooking and eating together, it’s also true that these elements do not imply any particular or exceptional appreciation of leisure time or a romantic appreciation of life.

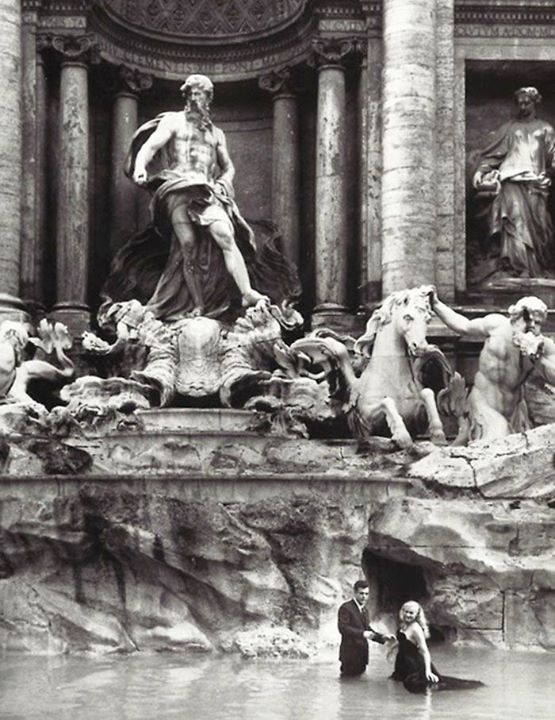

Of course, the most famous scene of the film, the scene in which Sylvia (Anita Ekberg) bathes in the Fontana di Trevi with a mesmerized Marcello, was destined to become an icon, because there is so much beauty in so few minutes of film! But this astonishment makes many forget, or not to see, the underlying sense of melancholy, in which is evident the distance between Marcello and Sylvia, from the real condition of life (Marcello) and from the dream (Sylvia, the American star), and this inescapably: despite the possibility for Marcello to achieve her, if only for a night, it would have been just a pause in the desolate frame of so deeply different lives.

Marcello Mastroianni, who has been Fellini’s alter ego for many of his films, is also one of the reasons for my love for this film, his allure, his ability to act so naturally and his charming indolence, he’s absolutely perfect for the role of a gossip columnist who arrived in Rome full of ambitions and then got lazy and disillusioned about his talent and his chances of success.

Going around in Rome, for his job and because of his curiosity, which I share even now at such a distance, and his fascination by a world, he meets actresses, noble women, intellectuals…a world that Fellini too imagines and inhabits. But the people he meets, this “circus” of humanity, don’t stop him from feeling always apart, and never able to take a step forward in his own life. But this is not a story about existential doubt or creative breakdown (we’ll have 8 ½ for this), it’s about the disorienting sensation felt in front of a world which is changing fast around him, a world which once looked full of possibilities, and brought him to move from the province to Rome, and where the American star had become a symbol of what was happening to Italian society in the moment in which it started to follow a social model which was not an outcome of its history.

This is also one of the central concerns of Pier Paolo Pasolini’s work (and it’s not by chance that he’s one of the scriptwriters. But I will write later a post dedicated to him). It’s about the process of loss of identity and purpose in my country, in what was a sort of cultural, economic and social revolution which left behind centuries of life shaped by agricultural work and the work of artisans workshops and which brought the progressive abandonment of thousands of little towns for the big cities and a very different world.

Of course it was not only a sort of “American dream”, or the capitalistic model spreading in Italy and beyond, but it was about the process of late and accelerated industrialization and of “modernization” (with many doubts and confusions about what this could mean) which brought with it deep changes in social relations and in the way in which Italians had been living for centuries. From a life shaped by the seasons, by the slow turning of years, the diurnal marking of time in the regulation of work in the fields, and the routines of daily life lived in little towns through generations (Italy was a country of thousands of independent little cities), to the working processes of large commerce, the scheduled timetable of industry and machines, of great and complicated cities .

“La Dolce Vita” reflects this existential conflict but at the same time it looks at those who gained, those whose privilege came from these changes, like intellectuals who found the possibility to live from their intellectual works, even live well from it, but got lazy, lazy about their social role to keep alive a counter culture, other voices, and questioning (Paolo Sorrentino’s ”The Great Beauty” lives in the penumbra of “la Dolce Vita” brilliantly parsing its critique in a world become yet more enervated in the years that had passed between the two films and without the false hope).

Central to this description is the fascinating character of Steiner (Alain Cuny), the intellectual friend of Marcello with his perfect family and perfect friends.

I was a teenager when I watched this film for the first time and I remember vividly the great admiration that my naïve mind had for him. A sophisticated, educated man with a beautiful family, house, friends, he was somebody to admire – until he kills his two children and then himself. It seems curious now but at that time this epilogue strangely didn’t touch me, maybe because of a teenage passion for heroic dramas or because I gave more importance to the beauty that he made in his life.

This presence continued to be in my thoughts, but then my approach to cinema has always been without filter, as though absorbed through the skin, through sensibility and pleasure.

In fact, Steiner has been an obsessive and recurring presence in my imagination as a sort of sophisticated reference to an elegant brilliant life.

Actually, very recently, he began to come again to my mind each time I met people with seemingly great potential but without any real longing for social engagement, and I looked back to him, I watched and listened again to his conversation with Marcello who, spending his days in the vacuity that I described, asked him to come back to visit more often because he would have loved to spend more time in Steiner’s idyll, his world, and because of his admiration for him, an admiration like mine. But Steiner, refusing Marcello’s admiration, confesses that he’s just not bright enough, or brave enough, to challenge real life, and that his impossibility to live fully has made him envious even of the most miserable of real lives. He says that he cannot live life with passion, like in an art work in its enchanted order, like the life that he has constructed. But he goes further, when he looks at the world, where everything at that time for so many could look so positive, so full of hope and ambition, and he sees only a fake place with dramatic turmoil underlying it.

We can say that he was warning of his own dreadful act but it had the effect of pointing out a collective drama that Italy was silently living in the light of accelerating economic expansion, an alienation vividly represented in the film by the several bleak landscapes of the new modern districts in Rome, a landscape replicated many thousands of times over across Italy since then, the buildings no longer modern, now just dreary and clumsily chaotic. Of course, this time was still a fertile one of thought, of engaged intellectuals, artists, music, but the vision of Steiner was on the future, the time in which his children would have been adults. And so, almost as a premonition, he saw the kind of world that they would have lived at the beginning of the 80s, and the feeling of being completely unable to stop the progressive cultural and social decline in Italy.

This is why this film talks to my present, because if I was a child during the 80s, I’m also still living through the outcome of this process, I’m living the sense of real instability and general pessimism, of a blocked society where many of the social achievements made by previous generations are slowly disappearing and where every year more than 100.000 Italians prefer to escape, to be some other place, away from here. Not only because they can’t find work but because of the sensation of living in a society in which the odds are stacked against us and every simple mundane thing, every transaction, every exchange, involves negotiation and complications, from going to the post office…to the outcome of a date! And this didn’t begin with the virus, it is a contagion that has been incubating in the society for a very long time now, sometimes breaking out, and sometimes quiet. And, maybe, Steiner imagines that we carry it within us. Or maybe he doesn’t, but we do.